- Article Category

- IRS Form 5471

Updated Posted

Minimultinationals Chapter 01: Overview of the Series

Phil Hodgen

Attorney, Principal

Share

American minimultinationals are small (for various definitions of "small") business enterprises subjected to the U.S. tax system.

There are many ways that a minimultinational becomes exposed to the U.S. tax system. Doing business in the United States is an obvious way. If you have an office or employees in the United States, some portion of your business profits will be taxed.

I focus here on businesses that operate mostly or entirely outside the United States but are owned by U.S. citizens or residents. This factor alone--ownership by a U.S. person--means that the business profits will be exposed to U.S. income tax, even if the business never operates in the United States.

In this chapter I give a brief overview of the reasons--technical and practical--why tax planning is so brutal for minimultinationals.

Then, I introduce you to my "Buckets and Pipes" theory1 of tax planning. Plumbers make sure that water flows where it is supposed to go, without leaks. Tax lawyers create plumbing systems so money can flow from one place to another.

I conclude with a global view of all of the types of business structures there are. Or, at least, I list every genus that I can think of, because species variations within a genus are infinite.

Why Tax Planning is Brutal for American Minimultinationals

In brief, because tax law is borderline insane, you're dealing with multiple countries' worth of insanity. Megacorps can buy their way around the problem, but you can't.

Let's explore, shall we?

Many Crocodiles in the River

The first (and obvious) reason that minimultinationals face problems with tax planning is because there are multiple countries who assert the right to tax business profits.

Most countries have a residence-based system of taxation: if you live here, or if you do business here, we will tax your income. Our American minimultinational owner living and doing business in France would probably (in the eyes of the French tax collectors) look like a resident and be asked to pay French income tax personally, and business profits would be taxable in France as well.

The United States asserts the right to tax its citizens and residents (green card holders, for our purposes) on all of their income, no matter where those citizens or residents happen to be on the planet. So our American minimultinational owner in France pulls a salary from the business? The United States expects to see some U.S. income tax paid on that salary, barring some workaround that might prevent tax--and there are workarounds.

Congressional Fiction and Your Money or Your Life

Income tax on our American minimultinational owner's salary is not what we care about. We care about the business profits.

The minimultinational is an active business enterprise with operations and customers entirely outside the United States. Wherever it is operating, this same "taxation based on residence" concept will apply to the minimultinational. "Resident" corporations are defined in a host of ways by different countries' tax laws. But with certainty: if a business is operating in a country (employees, offices, customers, etc.), it will be a resident under almost all definitions, and its business profits taxed there.

The United States also asserts the right to tax the business profits of that business enterprise--even if the business activities never touch the United States. In Chapter 2, I will give you the gory technical details. But for our purposes it is sufficient to say that almost all business profits of an American-owned minimultinational will be taxable in the United States.

How does the United States assert the right to, for instance, tax the business profits of a French corporation doing business entirely in France?

Quite simply, it doesn't. The French government wouldn't put up with that claim for a minute. Instead, the U.S. government relies on its right to tax U.S. citizens and residents.

If you are a U.S. citizen and you own all of the shares of a French corporation, U.S. tax law creates a fiction:

"Let's pretend that all of the profit earned by your French corporation is somehow magically distributed to you, the U.S. citizen human, even if no money was in fact ever distributed to you. Guess what! You personally have taxable income and must pay U.S. income tax on that."

Now the U.S. citizen human--our American owner of a minimultinational--is faced with a classic "Your money or your life" situation. U.S. tax law, via a self-created fiction, forces the American to either pay U.S. tax on the French corporation's profit, or go to jail for tax evasion.

Downside Risk

The United States has created a system where--to use my patented "buckets and pipes" metaphor--we pretend that profits flow smoothly from a foreign corporation to a U.S. citizen's personal income tax return, where those foreign profits are taxed.

Legislative fiction begets complexity. Or, to quote noted international tax scholar Walter Scott:2

Oh, what a tangled web we weave

When first we practise to deceive!

Now that we have introduced a fiction, we need more fiction, workarounds, and exceptions to solve the problems that our original fiction created.

And this creates risk for the minimultinational. The rules are baroque, and over any considerable period of time Congress makes them worse—never better. You are quite likely to get it all wrong.

And getting it wrong does not just cost more tax. Getting it wrong will cost more penalties. There are a host of penalties in tax law generally, because we are a Nation of Puritans who believe in Punishing the Iniquitous.

As a general proposition in international tax matters, the rule of thumb is simple:

Accidentally missing a piece of paper that the government wants you to give them is a $10,000 penalty, minimum.

I remember well the first project like this that I worked on as a Young Tax LawyerTM. A small ($10M per year) company had three even smaller subsidiaries in three different European countries. They didn't know about Form 5471, so had never filed it. An audit occurred. The Revenue Agent discovers the problem. Three missing Form 5471s times three tax years ("Lemme tell you how nice I'm being to you") equals $90,000 of penalties. Hilarity ensued.

Imagine getting a gratuitous invoice from the IRS for $90,000, with the implicit "Your money or your life" threat behind it. A minimultinational cannot stand too many cash flow hits.

Talent

Tax law is complicated enough. The international tax rules are an overlay on top of the regular tax laws. So if you have a corporation, you look at Subchapter C of the Internal Revenue Code plus Subchapter N (the international stuff). If you have a partnership, it's Subchapter K plus Subchapter N. And I'm not counting the gratuitous misfiled and hidden little gems littered about the Internal Revenue Code that you need to remember.

Finding people who are good at this stuff is hard. Very hard. They tend to be overworked. And expensive. Accounting requirements, legal fees, and tax return preparation costs balloon disastrously when an American business goes international.

You Can't Solve This Problem With Money

Bluntly put, a minimultinational cannot buy its way out of the tax problem—even with a total willingness to pay whatever tax is owed. (And I highly recommend that you file tax returns on time and pay the tax on time. Live free.)

Google can "lobby" politicians. You, dear minimultinational owner, will never see enough money in your lifetime to turn the head of a Federal politician.

Google can pay for cubicle farms of people to analyze and manage its tax affairs. You can't.

So you're going to have to be smart. Sometimes you need the Regular Army. Sometimes you need ninjas. Google has armies. You need a ninja or two to fight this battle.

Structure Overview

It's all Buckets and Pipes.

Humans, when you look at it, are simply self-propelled filtration devices designed to ingest coffee and then . . . well, you get the idea. :-)

Businesses are the same. What is a business but a method for moving money from one place (a customer's wallet) to another place (an entrepreneur's wallet)? This is an honorable and valuable human activity. Flowing the other way--from the entrepreneur to the customer--is the creation of value in the eyes and heart of the customer. The customer is demonstrably better off in the transaction. That is why the customer willingly exchanges money for a product or service.

So if we look at businesses as a flow of money (in one direction) and value (in the other direction), it's easy to see where tax planning fits in.

Tax planning is the creation of financial plumbing to move money from a customer to the entrepreneur with minimum leakage.

There are two types of leaks. One is tax. The other is the transaction cost of creating and maintaining the financial plumbing system: accounting, tax returns, penalties, clever tax lawyers like me, and adjusting the plumbing system to random new tax laws created by non-Skin in the Game3 politicians.

Create your business structure to minimize leaks and make it adaptable to whatever our friends in Washington DC choose to do. Well, as adaptable as possible.

The Received Wisdom in international tax planning for many decades until December 2017, was deferral. Set up a foreign corporation, do business through that corporation, and avoid various landmines hidden in the Internal Revenue Code.

If you did that, that foreign corporation's business profits would not be immediately taxable in the United States. The business profits would only be taxed in the United States when, for instance, the foreign corporation paid a real dividend to its U.S. shareholders.

In December 2017, Congress took all of the puzzle pieces, put them back in the box, shook the box, and dumped out the pieces and said "start over". American entrepreneurs abroad with decades of business operations and retained earnings suddenly faced an enormous tax bill. "Come to Jesus" indeed. I saw people who faced retirement ruin because of this. Apple and Google bought the right kind of law for their purposes. The minimultinationals of the world were simply collateral damage. (I'm talking about Section 965, if you want to ask the internet about this specific tax law).

Your financial strategy should not rely on Congress for success. They don't care about you.4

The Universe of Choices

It's easy to catch a fish. Just drain the lake and pick up the fish you want.

Similarly, it's easy to pick the right business structure. Just list the entire universe of possibilities and cross off the ones that don't work.

Here are all of the types of business structures that I can think of. Over the course of this series we will talk about all of them. We will be looking at how efficient they are--as financial plumbing.

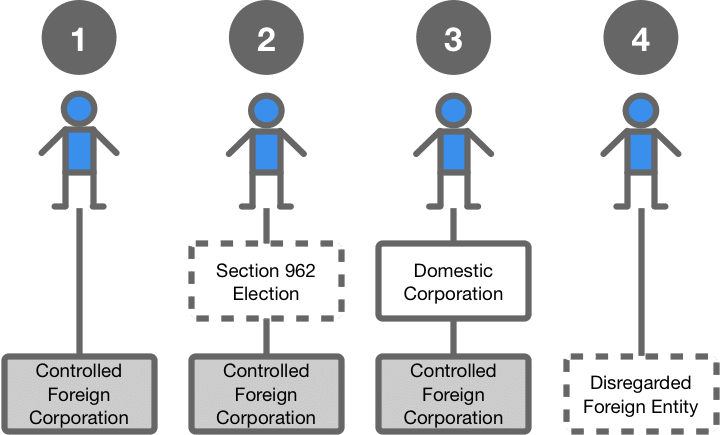

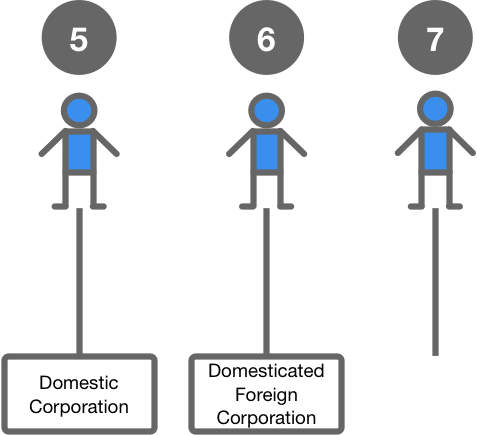

For our purposes, assume that we have a single-owner minimultinational. Here are the structure choices:

That's the bait to keep you subscribed. I will talk about each of these structures in upcoming episodes.

Next Time

Why U.S. tax law is so pernicious: a simple explanation of Subpart F income and GILTI. I am going to acquaint you with the way the U.S. system works so you know what you're dealing with.

And I'm going to live dangerously. I will limit myself to two pieces of tax jargon ("Subpart F" and "GILTI") and attempt to limit myself to words with one or two syllables. Let's see how that works!

- Patented, trademarked, copyrighted worldwide, protected by barbed wire, starving hyenas, a moat filled with crocodiles, and your grandmother's disapproving gaze. ↩

- Walter Scott, Marmion, Canto VI, stanza XVII. ↩

- Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb ↩

- YouTube. Don't click on this link if potty-mouth words offend you. Places like this and bands like this (and specifically this band) occupied most of my free time in law school. I'm better now, thank you very much. ↩