- Article Category

- IRS Form 5471

Updated Posted

Minimultinationals Chapter 02: It's All Taxable to You

Phil Hodgen

Attorney, Principal

Share

Introduction

All of the profits generated by a minimultinational enterprise will be exposed in real time to the U.S. tax system. Chapter 2 explains why.

We will talk about how the U.S. taxes those profits in future installments of this book. Different business structures have different tax results.1

Recap

What's a minimultinational?

Let's recap. A minimultinational is a small business that:

- Has U.S. owners; and

- Generates its profits outside the United States.

"Small" is relative. A minimultinational might have sales in the hundreds of millions or the hundreds of thousands.2

Who this is for?

This series is for owners of minimultinationals. American entrepreneurs.

What question does it answer?

"What business structure should I choose in order to minimize U.S. tax?"

All your profit are belong to U.S.3

Summary

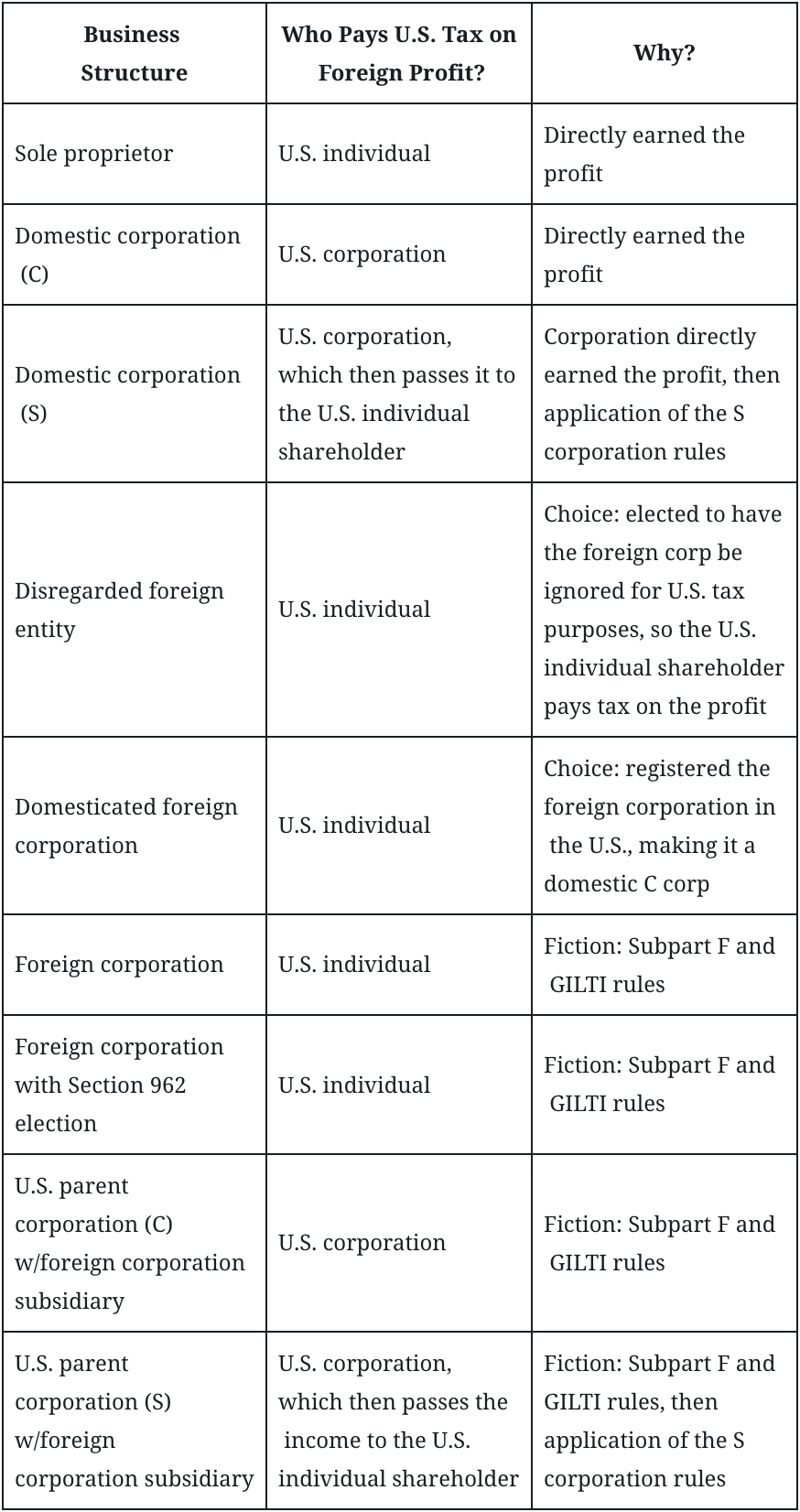

No matter how you set up your business—corporation, partnership, LLC, or sole proprietorship—its foreign-generated business profit will be taxable to you in the United States in the year that it is generated:

- Reality. Because you (or a U.S. entity you own) actually earned the profit.

- Choice. Because you (or a U.S. entity you own) chose to be treated as earning the profit.

- Fiction. Because you (or a U.S. entity you own) is treated by U.S. tax law as if you (or the entity) actually earned the profit.

Reality: foreign profit is earned directly by a U.S. person

It's easy to see how the U.S. has the right to tax income actually earned by a U.S. person. I receive a salary, so I pay tax on it. A U.S. corporation sells a product (to anyone in the world), so it pays tax on the profit.

If the business is a U.S. person, then the business profits are taxed in the United States.

Sole proprietor

This is you, as a human, doing business. You live in Burkina Faso and provide a service or sell a product to someone in Burkina Faso. In tax jargon, you are a sole proprietor. Your Burkina Faso business income will show up on your personal U.S. income tax return (Form 1040), via Schedule C.

U.S. corporation

You own a U.S. corporation and live in Burkina Faso. Your U.S. corporation provides a service or sells a product to someone in Burkina Faso. (You are an employee of the corporation and do the actual hands-on work). The profit is reported on the corporation's U.S. tax return (Form 1120 or Form 1120S).4

Choice: you choose to make the foreign profit be taxable to a U.S. person

Doing business as a sole proprietor is probably a bad idea for a variety of practical reasons. So is trying to conduct business operations abroad using a U.S. corporation. Good luck getting a business bank account in Burkina Faso for your Illinois corporation. :-)

Usually, you will want to set up a local business entity—a corporation, typically—where you are living and doing business. Even if you use a foreign corporation, you can choose to make its business profit be taxable directly in the United States. Here are two strategies for doing that.

Foreign corporation, disregarded

You form a corporation in Burkina Faso, where you live. You make a special U.S. tax election for that corporation.5 The Burkina Faso corporation provides a service or sells a product to someone in Burkina Faso.

The U.S. tax result is exactly the same as the sole proprietorship: the Burkina Faso corporation's net income is reported on your personal U.S. income tax return (Form 1040) via Schedule C.

Foreign corporation, domesticated

Take your foreign corporation. Follow a special procedure in Delaware to register your foreign corporation there.

Now the foreign corporation is like a dual-citizen individual.

- The other country sees the corporation as a foreign country corporation, and taxes the corporation's profits according to that country's normal rules.

- For U.S. tax purposes, the IRS views the foreign corporation as a domestic (Delaware) corporation. The foreign corporation files Form 1120 ("I'm domestic!") and reports its profit.

Fiction: U.S. tax law pretends the foreign profit is "earned" by a U.S. person

Sometimes the foreign business profit is treated as if it is earned by the U.S. owner because of a fiction created by U.S. tax law. A foreign corporation, for instance does business—provides a service or sells a product—outside the United States. But U.S. tax law pretends as if the U.S. owner of that foreign corporation earned the profit.6

Foreign corporation

Let's take our average American entrepreneur: a U.S. citizen living abroad decides to start a normal business and, like everyone else, forms a corporation in that country through which to do business.

There are only two types of income that this foreign corporation can earn:

- Passive income. Income that is generated from assets owned by the foreign corporation. E.g., rental of real estate, dividends received.

- Active income. Income that is generated by active business activities (services, product sales) conducted by the foreign corporation.

Except for situations you can probably ignore, all of the foreign corporation's profit will be reported—somehow—on an American income tax return.7 Active or passive. It doesn't matter.

Foreign corporation variants

Not that it matters for this discussion, but I want to throw a couple of pictures at you, just because there are eight basic structure choices for a minimultinational, and these are the final three.

In all three of these variants, a foreign corporation is the operating entity. The only difference is in the shareholder. This means that the only difference is how the foreign profit is taxed when it reaches the U.S. shareholder. That is something I will talk about in future chapters. But for now, here are the other alternatives you will be considering.8

- Section 962 election. Here, the individual U.S. shareholder is still the same as the normal structure, but the individual is taxed differently because of the special tax election.

- Domestic C Corporation owns Foreign Corporation. Here, the domestic corporation is taxable on the foreign corporation's profit.

- Domestic S Corporation owns Foreign Corporation. The domestic corporation is taxable on the foreign corporation's profit. The domestic corporation is an S corporation. Because the individual is taxable on the domestic corporation's income, the foreign corporation's profit is ultimately taxable to the individual shareholder.

The two fictions

There are two fictions that make business profit earned by foreign corporations (or the variants I described above) taxable to the U.S. owners:

- Passive income earned by a foreign corporation is called "Subpart F income" in the Internal Revenue Code. U.S. shareholders have been immediately taxable on that kind of income since 1962.

- Active income earned by a foreign corporation is called "GILTI" in the Internal Revenue Code. U.S. shareholders have been immediately taxable on that kind of income since 2018.

It ain't right

You live in Burkina Faso. Let's make your business as local as possible: you form a corporation and set up shop to provide business consulting services to local companies.

The United States government claims the right to tax your foreign corporation's business profits, even though the business has no contact with the United States — except for you and your U.S. passport.

But that's how it works

The U.S. does not have the power to directly tax a business operating in another country: international sovereignty still means something. Just like your local drug dealer jealously guarding his turf, governments jealously guard their right to extract revenue from people and businesses on their turf. With bullets, if necessary.

Your foreign corporation will pay normal tax in the country where it operates. The U.S. won’t touch the foreign corporation itself. Borders. Army. It's unlikely that the Burkina Faso government would be amused if an IRS Revenue Agent showed up to collect tax from a Burkina Faso business.

But the U.S. does have the power to tax you—the U.S. owner of a foreign corporation—by wielding the usual “Your money or your life” threat.

Federal law contains two rules that create "let's pretend" income for you (even if you receive no cash). On which you will pay very real U.S. income tax, or go to jail. Your money or your life, indeed.

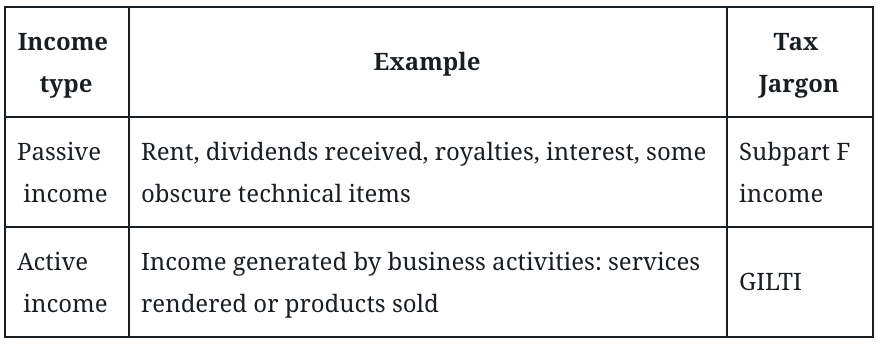

The two profit categories

The two "let's pretend" categories of profit are:

In Ye Goode Olde Days™ the categories mattered more, because active business income did not get taxed until you paid the money from the foreign corporation back to the U.S. That's more or less gone away now, effective January 1, 2018. Now everything (for certain defined values of "everything") is taxable.

Passive income (Subpart F)

You create a foreign corporation for your business. The foreign corporation owns an asset and collect income from it, with little/no work. That's Subpart F income.

Example

Your foreign corporation owns a warehouse. It uses half of the warehouse for business operations, and rents out the other half to a tenant. The rental income is Subpart F income.

That, in a nutshell, is the definition of Subpart F income. U.S. shareholders are taxed on their share of a foreign corporation's Subpart F income.

Example

You own 40% of a foreign corporation. The foreign corporation has $100,000 of Subpart F income in 2019, and does not pay you a dividend. You must report $40,000 of Subpart F income on your 2019 U.S. personal income tax return, and will have to pay income tax on that income.

Fake income, real tax liability.

The definition of "Subpart F income" is actually broader than this. There are other types of income that are tied to Clever Lawyer Tricks™ or specific types of business operations (shipping, oil and gas, etc.). This falls into noise category.

The Clever Lawyer Tricks™ were designed to convert—under the pre-2018 tax laws—immediately-taxable Subpart F income into NOT immediately-taxable ordinary business income. Since a foreign corporation's ordinary business income is now GILTI—and immediately taxable—there is less value in pursuing Clever Lawyer Tricks™ because you cannot postpone income.

Active income from business operations ("GILTI")

Foreign corporation profits from normal business operations will be immediately taxable to its U.S. shareholders. This is the intention of the GILTI rules.9 Those rules pretend that the U.S. shareholders actually earned the foreign corporation's active business profits, and will owe U.S. income tax on those profits.

The usual "exceptions exist" caution should be remembered. But for strategic tax decision purposes, assume that no exceptions apply to you.

One deceptively attractive exception says that a certain amount of the foreign corporation's net profit will be tax-free.

The tax-free part of the foreign corporation's net profit is computed by reference to its hard assets (machines, buildings, etc.). If your foreign corporation has a lot of these assets, you can get a portion of the net profit treated as tax-free for U.S. purposes.

For you math fans, here's how it works:

- Look at the company's assets. Compute the depreciated basis of those assets.

- Multiply that by 10%.

- That's roughly how much of the foreign corporation's profit will be tax-free in the United States.

Example

Your foreign corporation has a factory full of machinery, and the depreciated basis of the machines is $1,000,000. Ten percent of that is $100,000.

You may (after a lot of "what if?" and "but" and "except for" hurdles) be able to take up to $100,000 of your foreign corporation's active business profits tax-free.

In real life, I don't think this exception matters for minimultinationals. If you are General Motors and you have a manufacturing facility in Brazil with hundreds of millions of dollars of equipment, the numbers might look good. General Motors might be able to take home a bunch of Brazilian profit tax-free.

In my experience, minimultinationals range from "a digital nomad with a MacBook Pro" to . . . bigger than that. But even the big minimultinationals tend to be asset-light and brainpower heavy.

Or if they have assets, they are intellectual property rather than hard assets: machinery, buildings, etc.

This means that minimultinationals are unlikely to have much of their active business profit be treated as tax-free. If the total depreciated basis of assets is zero, the math is clear: zero x 10% = zero.

Passive or active: it's all taxable

Thus we can see that the tax rules for foreign corporations are simple: it doesn’t matter whether its income is passive (rental income, etc.) or active (selling things to customers at a profit). You, the shareholder are going to be taxed on the foreign corporation’s profit.

But wait! Google, Apple, and other Bloated Plutocrats are still using Clever Lawyer Tricks™ to avoid U.S. tax

Yes.

- They buy Senators. You don't.

- They have cubicle farms full of Dilberts toiling to shave 1% off their average tax rate. You don't.

- A 1% reduction in the average tax rate on $10 billion of profit creates a tax savings of $100 million. A 1% reduction in the average tax rate on your $10 million of profit yields a tax savings of $100,000.

How hard would it be for you, American entrepreneur, to go and generate $100,000 of profit instead? One new customer? One new product? One improvement in operating efficiency?

Keep it simple. Stick to your knitting.

Summary and Next Time

Where foreign business profit hits your U.S. tax return

In this chapter we talked about how foreign business profit inevitably hits a U.S. income tax return somehow. Here is the handy-dandy summary in table form:

Next up: how that business profit is taxed

In Chapter 3 we will start to talk about how the foreign business profit is taxed in the United States under all of the eight business structures described above.

- “If things were different, they just wouldn’t be the same”. Source: my dad, said to whining teenage me. Stopped me dead in my tracks, that sentence did. ↩

- Below that, we might want to call the business a "micromultinational". A U.S. citizen running a business from a MacBook Pro in a coffee shop in Chiang Mai is a micromultinational. The tax considerations are the same for micromultinationals as they are for minimultinationals—and indeed for juggernaut multinationals —but there isn't enough money to pay for complex tax engineering to solve them. ↩

- Sorry. Couldn't resist ↩

- U.S. corporations are either "C corporations" or "S corporations". This distinction is noise right now. That distinction will matter when we talk about how the income is taxed, in future installments. Right now, the only thing that matters is that the income shows up on a U.S. tax return. ↩

- Details will come in a future installment. Form 8832. "Check the box". Right now I am just showing you that taxable income shows up on your U.S. income tax return. Later we will talk about how that income is taxed. ↩

- You might see the possibility for a spot of unpleasantness here: the foreign country taxes the foreign corporation's profits, and in addition the U.S. taxes the owner—you—on the foreign corporation's profits. ↩

- Don't worry. I will tell you enough in future installments so you know why you can safely ignore these edge cases. ↩

- We're going fishing? Let's drain the lake, pick up all the fish, then throw away the ones we don't want. That's how I do tax planning. ↩

- “Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income". Ignore the acronym. It doesn’t matter what it stands for. ↩