- Article Category

- Cross Border Business

Updated Posted

GILTI: In Which Foreign Corporation Income is Made Taxable

Phil Hodgen

Attorney, Principal

Share

Poker players are always looking for tells -- inadvertent signals by their opponents. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has a tell. Our Federal government has told us what they think of us.They think we are incipient felons.If you had any doubt about our how our Federal Overlords view us, new Internal Revenue Code Section 951A should clarify things for you. This new law introduces a new acronym: GILTI. The calculation looks like this:

The calculation looks like this:

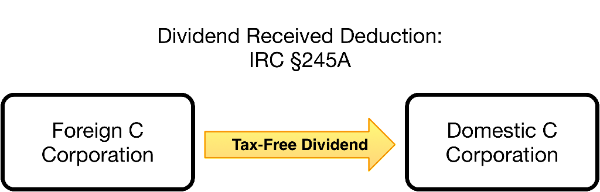

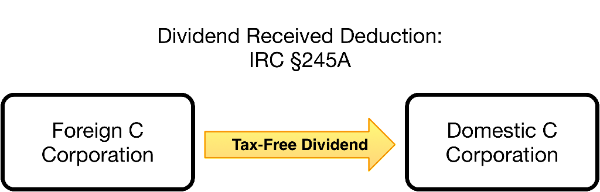

Pretty nice from Apple's point of view. And it is consistent with the philosophy of bringing foreign profits back to the United States without imposing U.S. income tax on those foreign profits.We can state the general principle, then: a U.S. corporation receiving a dividend from a foreign corporation will be entitled to a 100% dividend-received deduction, and therefore pay no U.S. income tax on that dividend income. Many exceptions and conditions apply, of course. This means that the dividend is fully taxable to the individual shareholder.

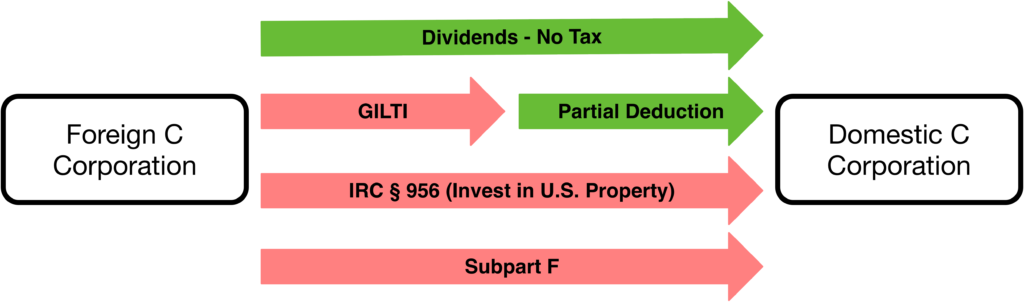

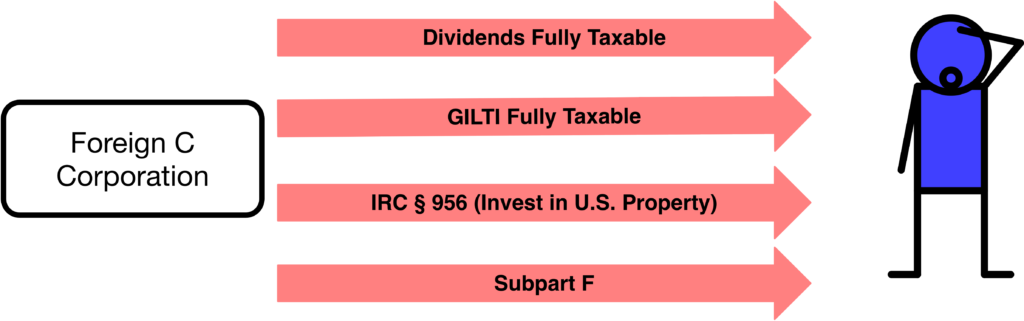

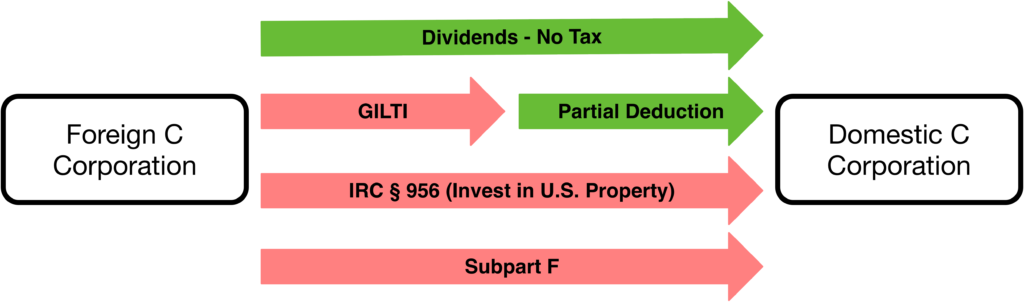

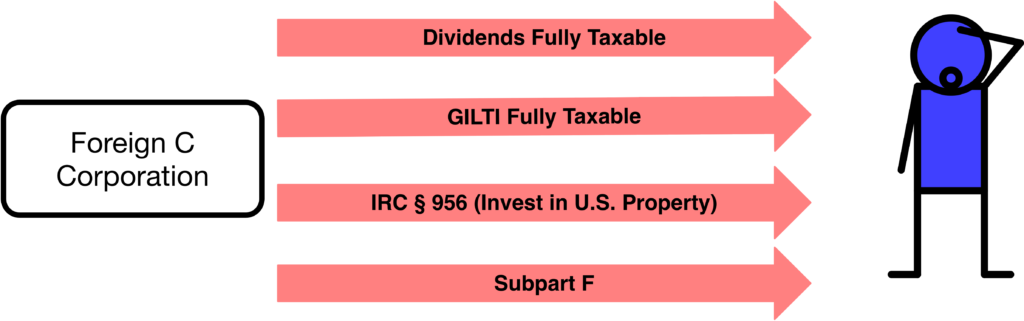

This means that the dividend is fully taxable to the individual shareholder. A U.S. corporation may be able to receive dividend income tax-free from a foreign corporation. Use IRC § 245A to accomplish this.A U.S. corporation will pay less tax on GILTI received (IRC § 951A) because of IRC §250.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable on Subpart F income.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable if something in IRC § 956 triggers taxation.By contrast, the situation for a U.S. individual shareholder of a foreign corporation looks like this:

A U.S. corporation may be able to receive dividend income tax-free from a foreign corporation. Use IRC § 245A to accomplish this.A U.S. corporation will pay less tax on GILTI received (IRC § 951A) because of IRC §250.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable on Subpart F income.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable if something in IRC § 956 triggers taxation.By contrast, the situation for a U.S. individual shareholder of a foreign corporation looks like this: Everything is taxable.

Everything is taxable.

Not Quite Territorial Taxation

The new tax laws are great if your name is Apple or Google.But for American entrepreneurs living abroad and running regular businesses, (tax) life is worse in 2018 than it was in 2017.The signature feature of the new tax law is that the United States has (in theory) changed to a territorial system of taxation for corporations.The new tax laws are worse than the old tax laws for American minimultinationals.Worldwide Taxation

Previously, a U.S. corporation would be taxable on its worldwide income. This was the basic premise of U.S. tax law, since forever.Predictably, clever tax lawyer tricks meant that this did not, in fact, always happen. Proof: look at the constant stream of news reports and moralizing over the last few years about Apple, Google, and big pharma with hundreds of billions of dollars of foreign profits that were untaxed in the United States.Territorial Taxation

So Congress changed the law in late 2017. We now nominally have a territorial tax system for corporations.A territorial system of taxation boils down to a simple concept: pay tax in the United States on profits earned in the United States, and do not pay tax in the United States on profits earned outside the United States.Exceptions Eat the Rule

However, the new tax laws do not really give us a territorial system of taxation--even for Apple or Google. "All dividends received from foreign corporations are tax-free." Except for the myriad of exceptions that make income taxable.And for American minimultinationals, the new tax laws actually make much--sometimes all--of the profit from their foreign businesses immediately taxable in the United States. Life gets worse, not better.The Promise: Tax-Free Dividends From Foreign Corporations

New Internal Revenue Code Section 245A creates the tax-free treatment of dividends from foreign corporations. A U.S. corporation that receives a dividend from a foreign corporation is entitled to a 100% dividend received deduction.1Old Rules

In the Good Old DaysTM if Apple received a dividend from one of its foreign subsidiaries, it would have regular taxable income. Apple would pay income tax, and whatever was left over could be paid out as a dividend to Apple's shareholders.New Rules for U.S. Corporations

Now, things are different. In calculating its taxable income, Apple gets a made-up tax deduction2 equal to 100% of the dividend its received from its foreign subsidiary. The calculation looks like this:

The calculation looks like this:| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Dividend Income | $1,000 |

| Less Dividend Received Deduction | -$1,000 |

| Taxable Income | $0 |

New Rules Don't Apply to Humans

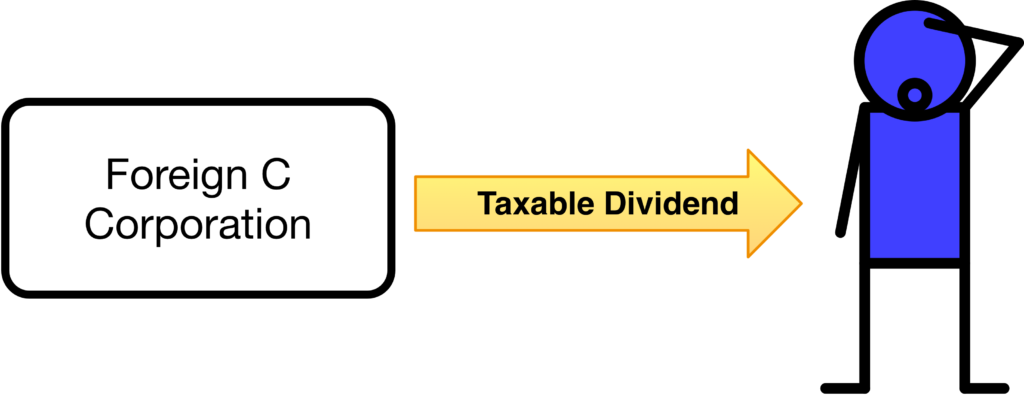

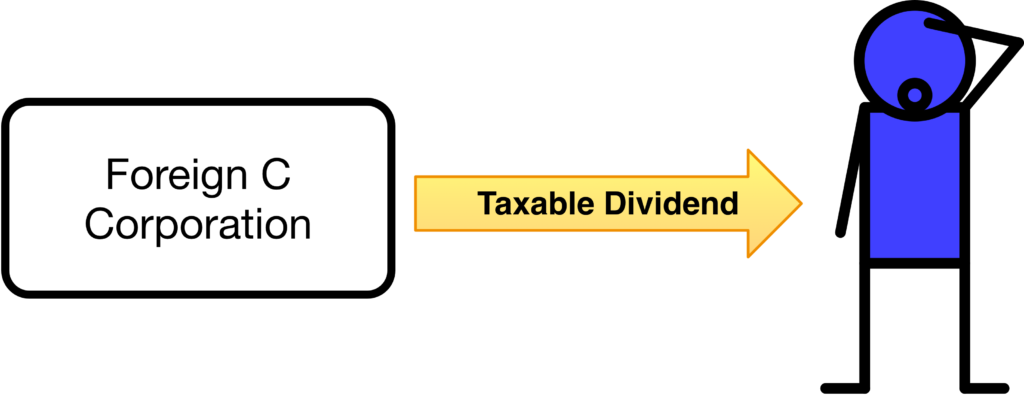

New Section 245A does not apply to humans who own stock of foreign corporations. If a foreign corporation pays a dividend to an individual shareholder, the dividend-received deduction is not available. This means that the dividend is fully taxable to the individual shareholder.

This means that the dividend is fully taxable to the individual shareholder.Old Exceptions Linger

The news is not uniformly fabulous for U.S. corporations and their foreign subsidiaries. Even though (in theory) a foreign corporation can earn $1,000 of profit and the U.S. parent corporation can receive that profit in the form of a tax-free dividend . . . in reality there are some exceptions.These exceptions can create taxable income. So what if IRC §245A promises tax-free dividends? The left hand gives you a tax break, and the right hand gives you taxable income.Subpart F Creates Taxable Income

If foreign corporations earn "bad" income, U.S. shareholders in those foreign corporations are taxed immediately on that income--whether or not the foreign corporation pays a dividend to the U.S. shareholder. These rules are found in Subtitle A, Chapter 1, Subchapter N, Part III, Subpart F of the Internal Revenue Code. Tax lawyers therefore refer to these as the Subpart F rules.You can have taxable income and have to pay a (cash) income tax without receiving any (cash) income."Bad" income is passive income: rents, dividends, interest, royalties, etc.The Subpart F rules survived the December 2017 rewrite of the Internal Revenue Code. So if a portion of a foreign corporation's profit is "bad" income, the Subpart F rules are going to pretend that the shareholder received some taxable income (the "bad" Subpart F income).IRC § 956 Creates Taxable Income

There is another legacy tax rule that survived the December 2017 rewrite. In the Good Old DaysTM an American could form a foreign corporation and earn profits in that foreign corporation. As long as the foreign corporation did not send that money back to the United States in some fashion, the foreign profits remained untaxed in the United States.Remember that: the key to not paying tax in the United States on foreign profits was to not bring the profits back to the United States.Predictably, U.S. businesses would have lots of cash in their foreign subsidiaries, and would have a need for cash to fund operations in the United States. So there was an itch to bring the money back to the United States.Clever tricks by taxpayers begat countermeasures by Congress. One of those countermeasures was Internal Revenue Code Section 956. If foreign profits of a controlled foreign corporation are invested in U.S. property, then the U.S. shareholder will have taxable (in the United States) income to the extent of that investment.A simple example? Well, we know that a dividend paid from the foreign subsidary to the U.S. parent would be taxable income (under the pre-December 2017 rules). So . . . the foreign subsidiary can lend money to the U.S. parent company, right?Wrong. This and many other back-door methods were the target of IRC § 956. Congress and the Internal Revenue Service did not fall off the back of the watermelon truck yesterday. They ain't dumb.For our purposes today (after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), the same risks continue: IRC § 956 is still in effect. Thus it is possible for a foreign corporation to shoot its U.S. shareholder in the foot by doing dumb stuff that causes taxable income to the U.S. shareholder--even if a tax-free dividend is paid to the U.S. shareholder.A New Way to Create Taxable Income

Congress introduced yet another way to convert tax-free income into taxable income: brand-new IRC § 951A.GILTI is an acronym for Global Intangible Low Taxed Income.3It is the Federal government's way of telling you what the appropriate profit margin is for a business: "We think 10% is an entirely reasonable rate of return." Watch for expansion of this attitude from Congress in coming decades.Here is how it works.- Calculate the income of the controlled foreign corporation. Special rules apply for how to do this.

- Look at the balance sheet of the foreign corporation. Find all of the tangible assets--things that can be depreciated. Don't include real estate.

- Using the depreciated value of those tangible assets, use a gratuitously complex formula to calculate a 10% annual profit on those assets. This slice of profit is not taxed and will be eligible to be paid out as a dividend and received tax-free by a U.S. corporate shareholder.

- All of the foreign corporation's income in excess of that 10% annual profit on tangible assets will be GILTI. This is a special type of income that is treated as immediately taxable to the U.S. shareholder.

Put It All Together

If you put it all together, the situation for a U.S. corporation looks approximately like this: A U.S. corporation may be able to receive dividend income tax-free from a foreign corporation. Use IRC § 245A to accomplish this.A U.S. corporation will pay less tax on GILTI received (IRC § 951A) because of IRC §250.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable on Subpart F income.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable if something in IRC § 956 triggers taxation.By contrast, the situation for a U.S. individual shareholder of a foreign corporation looks like this:

A U.S. corporation may be able to receive dividend income tax-free from a foreign corporation. Use IRC § 245A to accomplish this.A U.S. corporation will pay less tax on GILTI received (IRC § 951A) because of IRC §250.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable on Subpart F income.A U.S. corporation will be fully taxable if something in IRC § 956 triggers taxation.By contrast, the situation for a U.S. individual shareholder of a foreign corporation looks like this: Everything is taxable.

Everything is taxable.What This Means for the American Minimultinational

For the American minimultinational business enterprise (a U.S. citizen who owns a foreign corporation), everything has changed. There are three possible countermeasures that I know of:- Disregarded Entity. Make the foreign corporation a flow-through entity for U.S. tax purposes. Make an election using Form 8832 to have the corporation be a disregarded entity.

- Be like Apple. Form a U.S. corporation that will own your foreign corporation. Your U.S. parent corporation gets the tax breaks that Apple gets.

- Human Taxed Like a Corporation. There is a funny little rule (IRC § 962) that allows a human being to be taxed like a corporation on income from controlled foreign corporations. It's not perfect. But it may offer interesting solutions for you.