- Article Category

- US Real Estate Investments

- Published on

Branch Profits Tax for Rental Income

Phil Hodgen

Attorney, Principal

Share

This week I am writing about how rental income is taxed for nonresident investors in U.S. real estate, and when using a foreign corporation as owner of rental real estate we run into the branch profits tax.

Scenario

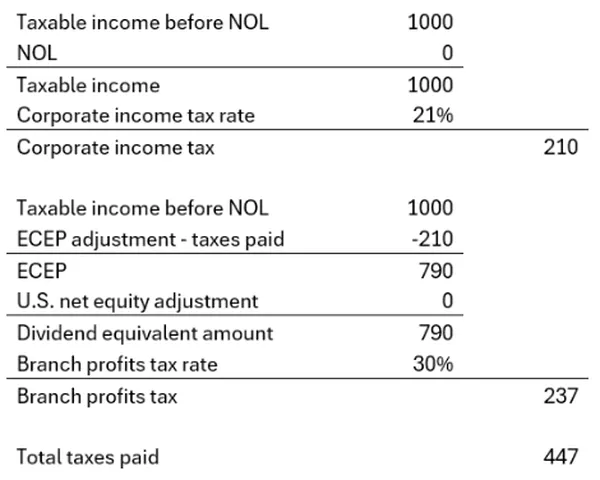

Assume that a foreign corporation owns U.S. rental real estate. Net rental income (rent collected minus expenses) for the year is $1,000. The foreign corporation has no other assets or operations anywhere in the world.

The problem: 44.7% Federal combined tax rate

Income tax

The foreign corporation will treat its rental activities as a “trade or business in the United States.” The rental income will be treated as “effectively connected” with the U.S. business activities of being a landlord.

This is the optimal income tax treatment for rental income. It will result in a Federal income tax rate of 21% (IRC Section 11) on the foreign corporation’s taxable income. IRC Section 882(a).

Branch profits tax

A second tax is imposed on the foreign corporation’s income: the branch profits tax. The tax rate is 30%, and it is imposed on a modified version of the foreign corporation’s earnings and profits called “dividend equivalent amount.” More on that, below.

The effect of these two taxes is to create a worst-case Federal tax liability of 44.7% of the foreign corporation’s taxable income.

Branch profits tax in a nutshell

A nonresident individual wants to buy U.S. rental real estate. Consider two corporate structures:

- Parent/subsidiary. The individual owns 100% of the shares of a foreign corporation, which owns 100% of the shares of a domestic subsidiary, which in turn owns the U.S. rental real estate.

- Branch. The individual owns 100% of the shares of a foreign corporation, which owns the U.S. rental real estate.

In the first structure, a dividend paid out of net rental income is paid by the domestic corporation to its shareholder, the foreign parent corporation. The default tax rate is 30% of the gross dividend. IRC Section 881(a). A subsequent dividend payment from the foreign parent corporation to its nonresident individual shareholder is not subject to U.S. income tax.

In the second structure, a dividend paid out of net rental income by the foreign corporation to its nonresident individual shareholder will not be subject to U.S. income tax. IRC Section 881(a) only imposes income tax on U.S. source income, and a dividend paid by a foreign corporation is foreign source income.

The branch profits tax is designed to create the same tax outcomes for the parent/subsidiary structure and the branch structure.

How to calculate branch profits tax

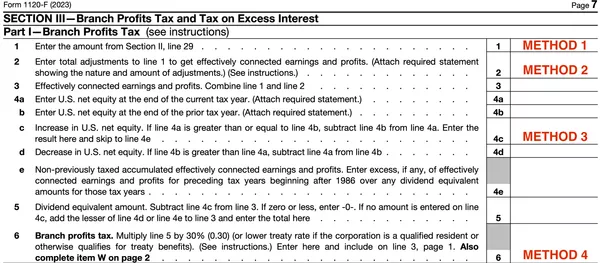

The branch profits tax is 30% of the foreign corporation’s dividend equivalent amount. Go look at Form 1120-F, Section III, Part I, line 5 (the dividend equivalent amount) and line 6 (the calculated branch profits tax).

The dividend equivalent amount is the foreign corporation’s effectively connected earnings and profits with some adjustments. It represents the foreign corporation’s ability to pay a dividend to the shareholder from its effectively connected earnings and profits. (“Effectively connected” earnings and profits means the earnings and profits are derived from the U.S. business operations of the foreign corporation).

Four methods to reduce/eliminate branch profits tax

There are four methods I can think of to reduce a foreign corporation’s branch profits tax imposed on rental income from U.S. real estate. If you know something I don’t know, please tell me.

Three methods reduce the dividend equivalent amount:

- Method 1. Reduce taxable income of the foreign corporation.

- Method 2. Accounting magic with the earnings and profits computation.

- Method 3. Invest in U.S. assets or pay down U.S. liabilities.

One method reduces the tax rate:

- Method 4. Use an income tax treaty to reduce the branch profits tax rate.

Method 1. Reduce taxable income

The first idea is to reduce taxable income. I know, this is blindingly obvious.

Why it works

The less money you make, the lower your tax bill will be.

Specifically for branch profits tax computation:

- Taxable income is the starting point for computing a corporation’s earnings and profits.

- Reduce taxable income, and you reduce earnings and profits.

- Earnings and profits will be the start of computing the dividend equivalent amount.

- Reduce earnings and profits, and you reduce the dividend equivalent amount.

- All other things held equal, a lower dividend equivalent amount means that the branch profits tax (30% of dividend equivalent amount) will be lower.

How you do it

Additional allowable tax deductions that are allocable and apportionable to the foreign corporation’s effectively connected income.

Consider a prudent and commercially-reasonable investment advisory fee paid to the individual nonresident alien shareholder. This will be a deductible expense for the foreign corporation and will not be U.S. taxable income for the recipient shareholder (because services are performed outside the USA).

Method 2. Earnings and profits adjustments

The second method for reducing branch profits tax will be earnings and profits. I confess that I am not a smart boy when it comes to the accounting arcana involved in tax accounting vs. earnings and profits vs. book accounting. I leave this more as a theoretical possibility than an actionable one. If you know stuff that I don’t . . .

Method 3. Increase U.S. net equity

This method is probably where you will spend most of your time. After building in a reasonable investment advisory expense (Method 1), you can do a lot to reduce or eliminate branch profits tax by having the foreign corporation acquire U.S. assets or pay down U.S. liabilities.

How it works

Remember that branch profits tax is 30% of the foreign corporation’s dividend equivalent amount. If a corporation makes capital investments or pays down debt, it has less cash to pay out a dividend.

Earnings and profits are unchanged but the cash on hand is reduced, so the foreign corporation has less money to pay a theoretical dividend to its nonresident alien shareholder.

The action for computing changes in U.S. net equity happens on Form 1120-F, Section III, Part I, lines 4a through 4e.

This requires understanding a few definitions. The objective will be for you to identify “U.S. assets” that the foreign corporation can acquire. Acquiring such an asset reduces the dividend equivalent amount dollar for dollar.

The alternate objective will be for you to identify “U.S. liabilities” for the foreign corporation to pay off. Paying liabilities, too, will reduce the dividend equivalent amount dollar for dollar.

Definition: U.S. net equity

U.S. net equity is what we are tracking: the change from last year’s ending number to this year’s ending number.

U.S. net equity simply means U.S. assets minus U.S. liabilities. IRC Section 881(c)(1).

Definition: U.S. assets

U.S. assets are assets used in the foreign corporation’s U.S. trade or business. IRC Section 884(c)(2)(A) says:

“U.S. asset” is defined in depth at Reg. Section 1.884-1(d)(1) (general rule) and (2) (specific asset types).

Cash as a U.S. asset

Bank deposits can be a “U.S. asset” for branch profits tax purposes. The amount of cash that qualifies as a “U.S. asset” is the amount needed for present operational needs. You can’t claim that a reserve for future expansion, for instance, is a “U.S. asset” for purposes of reducing the dividend equivalent amount.

See Reg. Section 1.884-4(d)(2)(v). It cross-references to Reg. Section 1.864-4(c)(2)(iii)(a), but the correct cross-reference is to Reg. Section 1.864-4(c)(2)(iv)(a). The government did a little renumbering of the Regulation in 1996 (see 1996-1 C.B. 154) but forgot to update the cross-reference in Reg. Section 1.884-4(d)(2)(v).

The short message here is that you can increase the foreign corporation’s cash position to reduce branch profits tax—if you can show that the amount on hand is needed for present business conditions. One example would be to hold a large cash position to buffer against fluctuating cash flow in the normal course of business.

Definition: U.S. liabilities

As you might guess, U.S. liabilities are those associated with the foreign corporation’s U.S. trade or business. IRC Section 884(c)(2)(B) says:

The eventual exit

The nice thing about plowing money back into U.S. assets is that it can permanently eliminate the branch profits tax.

No branch profits tax is payable in the year that a foreign corporation ceases doing business in the United States. Thus, when the foreign corporation sells its real estate investment, it files its final income tax return, checks the box at Form 1120-F, Section III, Part III, line 11a, and attach Form 8848. Branch profits tax is gone forever.

Roll your effectively connected earnings and profits into more U.S. assets, cash out and take the money home. Total Federal tax rate will be 21% only.

Method 4. Treaty tax rate reduction

The final way to manage branch property tax is to see if an income tax treaty can be invoked to reduce the branch profits tax rate from 30% to as low as 0%.

Look at Reg. Section 1.884-1(g) for the rules, and in particular look at Reg. Section 1.884-1(g)(3) and (4) for countries with treaties that have favorable branch profits tax rates.

Conclusion

Direct ownership of U.S. real estate by foreign corporations is, in my experience, problematic for tax and non-tax reasons. Your default structuring position should be to have a domestic entity to own title to the real estate.

Branch profits tax is the largest of the tax problems. A wholly-owned domestic disregarded entity (translation: LLC) doesn’t solve the problem. You need a C corporation.

What I find often is that the foreign corporation has a significant NOL from rental activities, therefore owes no income tax—yet must pay branch profits tax. And moving the real estate into a domestic subsidiary means you may have put that NOL out of reach: the foreign parent corporation has no more U.S. source income against which the NOL can be offset. All future income is earned by the domestic subsidiary.

I hope this little explanation has helped you understand the branch profits tax’s role in how rental income appears on a Form 1120-F and the two taxes that can apply.